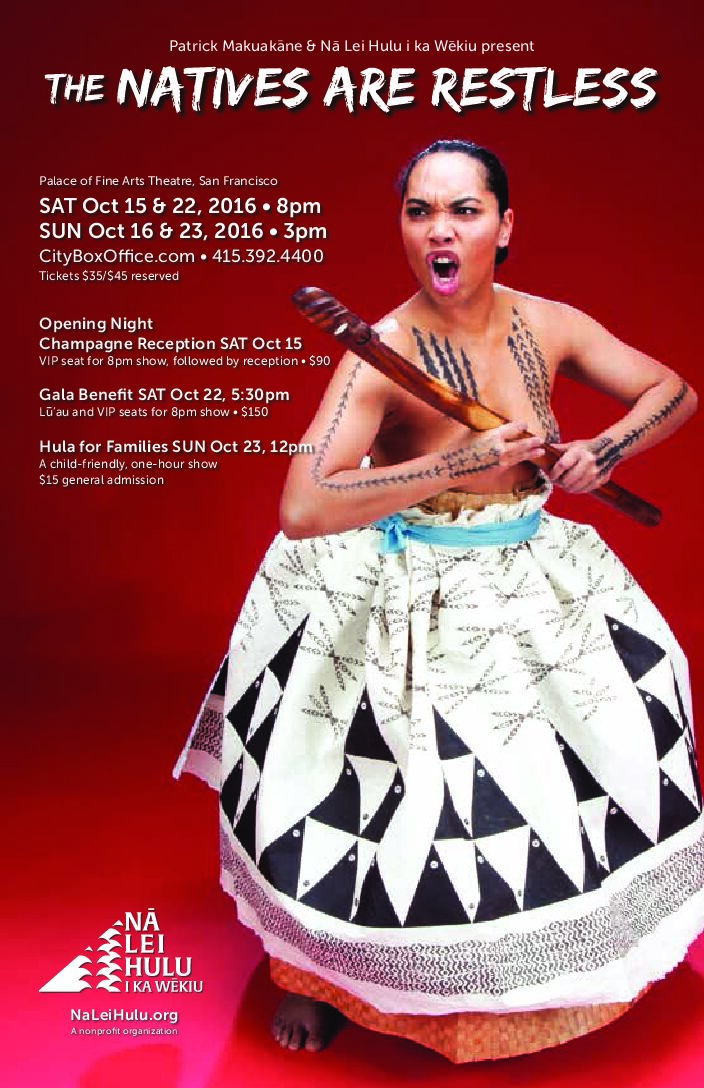

15 Oct The Natives are Restless

October 15-23, 2016 | Palace of Fine Arts Theatre

Sat Oct 15 Natives @ 8pm

Sun Oct 16 Natives @ 3pm

Sat Oct 22 Gala Event starts @ 5:30pm; Natives @ 8pm

Sun Oct 23 Hula for Families Show @ 12 Noon

Sun Oct 23 @ Natives 3pm

A Nā Lei Hulu favorite returns to the stage, reimagined

When The Natives Are Restless debuted in 1996, some audience members walked out. And

some respected authorities on hula were just uncomfortable with Kumu Patrick Makuakāne’s

dramatic break from tradition. But many dance critics could tell that they had witnessed

something ascendant. The Los Angeles Times praised the skill of the company and the

inventiveness of its “visionary leader.” Dance professor Angeline Shaka calls Natives “a hula

performance with teeth,” one that forces audiences “to confront the painful (and ongoing)

repercussions of Hawai‘i’s history of contact and colonization.”

Those teeth haven’t released their grip over the past twenty years. Makuakāne’s hālau

has performed Natives again and again since its bold debut. Each time it has evolved slightly.

And this year, Makuakāne is moved to bring Natives back, reconceiving the show more

dramatically than ever before. He’s left certain dances intact, changed others, and added an

entirely new second act to address the political and cultural issues now burning slowly through

the islands like a finger of Pele’s fire.

Act I

Natives begins with a booming voice cutting through the darkened theater. In a disgusted tone,

a man repeats missionaries’ real words about the Native Hawaiians—quotes that Makuakāne

found in their journals. “Can these be human beings? [They are] almost naked savages…haters

of God and inventors of evil things. The hula is a devil’s nest.” The curtain opens onto a

stunning tableau of two dozen bare-breasted and elaborately tattooed women of all ages,

shapes, and sizes, sitting regally on stage. Resplendent in bustled skirts, they perform a seated

hula with delicacy and beauty. The soft lights glance off their undulating arms and bare backs.

The voice that just boomed through the theater, decrying the “devil's nest” of hula,

conveys anger and vindictiveness. But the women are the embodiment of grace. The

disjunction settles on each audience member differently. Let’s just say that few come out on

the side of the missionaries.

Makuakāne’s anger at reading the missionaries’ journals sparked the creation of “Salva

Mea,” the centerpiece of The Natives Are Restless. The relentless rhythms of the song, by the

British band Faithless, were the perfect soundtrack for a rebellion that had roots in his

childhood. “I appreciate the rituals and the symbols of Catholicism—the singing, the clanging of

bells, the incense. But the precepts? The dogma? Forget it!”

In “Salva Mea,” the company of forty male and female dancers is buttoned up tight in

long-sleeved white shirts and long black pants and skirts. One of them plants a simple cross in

the middle of the stage. We have a church, a congregation. The music changes, and the dancers

are suddenly in a line spanning the stage, stamping their feet in unison and moving forward.

They twitch their torsos left and right. At times they hinge at the waist, their arms zooming up

behind them like demonic wings. At others they advance like a line of mercenaries,

expressionless.

A black-robed priest, played by Makuakāne, charges onstage. He singles out one dancer,

grabs her by the hair, and throws her over his bent knee. With a piece of charcoal he marks her

forehead with a cross, rips open her blouse, and brands her on her bare chest. Then, done with

her, he throws her to the ground and storms off. She struggles to get up, and, now disheveled,

stumbles back to the line. She has been symbolically raped.

At the end of the dance, the priest climbs onto a mount behind the crowd of dancers

and thrusts the cross upward. They cluster below him, reverent, a white circle of desperate

arms, reaching for redemption in a tangle of ecstasy, fury, ferocity, and docility. A native

population has gone from graceful to industrious to violent, from naked to neatly dressed to

wandering around in tatters, from fiercely independent to strangely malleable. The lights go

black.

Act I now ends with “Kaulana nā Pua,” a patriotic anthem protesting the 1893

overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. The song is also known as “Mele ʻAi Pōhaku,” the “Stone-

Eating Song,” because of a line in which the protesters say they would rather eat stones than

take the promises of the spurious new government (Ua lawa mākou i ka pōhaku / I ka ʻai

kamahaʻo o ka ʻāina, “We are satisfied with the rocks / The wondrous food of the land.”)

For a century, “Kaulana nā Pua” was considered so precious that dancing to it was

tantamount to disrespect for Native Hawaiians. By 1970, according to scholar Amy K. Stillman,

“that conception carried the force of an edict.”

But in The Hawaiian Journal of History, Stillman writes about new scholarship that

provided the perfect counter-argument—and catnip to Makuakāne. Two scholars revealed that

they found an account by a historian from 1895. He had interviewed imprisoned

counterrevolutionaries, who described the singing of the song as a way of honoring those who

had supported the monarchy. Apparently, the prisoners “beat out the rhythm, thumping their

drums and miming their scorn of the ‘heap of government money.’” They stamped their feet,

twisted their heels, slapped their thighs, dipped their knees, and doubled their fists. In short,

they performed the hula.

Makuakāne read the account of this discovery with great excitement. What about a

dance that pays homage to the prisoners, whose identification with the song was immediate

and visceral? If ever a dance could mix gravitas and aggression, this was it.

Act II

When the curtain goes up on Act II of the new Natives Are Restless, the first tableau takes us to

the year 2016 and a stunning assembly of people, overflowing into the wings. They are dressed

in the bright, primary colors worn by the protesters now making a mark in the islands—like the

multitudes who participated in the Aloha ‘Āina Unity March in August 2015. Some ten thousand

people crowded Kalākaua Avenue, turning Honolulu’s tourist boulevard into a sea of red T-

shirts; yellow banners; ti plants held aloft; and red, white, and blue Hawaiian flags. Marchers

stopped frequently to chant, sing, blow conch shells, and plead for their causes—from blocking

telescopes on Mauna Kea, a mountain sacred to Native Hawaiians, to forbidding GMOs in

agricultural lands. Their activism was a wave of the Sovereignty Movement, which at its core is

the argument that Native Hawaiians should have the same right to self-government and

indpependence that has been granted other Native American peoples.

Among the first words of the onstage protesters will be the first lines of the

contemporary chant “ʻO Ke Au Hawai‘i.” It imagines a day in which the descendants of the great

chiefly clans of Hawai‘i will rise up, proud of who they are, and continue in the great tradition of

their ancestors: Auē e nā ali‘i ē o ke au i hala / E nānā mai iā mākou nā pulapula o nei au e holo

nei / E ala mai kākou, e nā kini, nā mamo o ka ‘āina aloha, “O the chiefs of the past / Look upon

us, the descendants of this time / Let us get up, the multitudes, the precious children of the

beloved land.”

“Woe to the stones that have been strewn and scattered,” the chant goes on to say.

“Let the rocks be restacked so that a new home foundation can be made firm.”

Other dances in Act II celebrate recent efforts to rejuvenate the Hawaiian language and

to restore fishponds near Kāne‘ohe—an effort that combines ecology, economy, history, and

culture in one fell swoop. There will be “odd pairings” that Makuakāne says he enjoys inserting

into his shows and choreography, including a Hawaiian-language translation of the Beatles song

“Come Together,” reimagined by Puakea Nogelmeier and reimagined again by Makuakāne. A

piece praising ancient navigators will be paired with one praising the scientific stargazing that

takes place at Mauna Kea. In Makuakāne’s vision, science and stargazing might be able to

coexist with cultural traditions—perhaps on Mauna Kea, perhaps on some other mountaintop.

Like the original first act of Natives, the new second act will surely mutate, transmogrify,

and deepen over time, as Native Hawaiians continue to agitate and educate, to cry out in

protest and chant in homage to the ancients.